Description

The subjects Dalou treated during his English exile (1871-1879) were mostly intimate. They corresponded both to the shrinking of his circle of close friends – he had arrived alone with wife and child, in a country whose language he spoke poorly, and kept company with a handful of artist friends – and to the tastes of his English patrons: financiers or landowners, who saw in the French sculptor an artist in the tradition of the Houdon or Chinard as admired by their forebears. In the English capital, he embarked on a new career, thanks mainly to private commissions and the support of a network of patrons. On the strength of his success at the London Salons, and in particular those of the Royal Academy, Dalou became a renowned portraitist, much appreciated for his genre figures: maternities, bathers, women at prayer, children at play… The artist was sometimes seen as an innovator, sometimes as a classic. All his activity led to two major commissions: the Monument to the Memory of Queen Victoria’s Grandchildren and a public monument, Charity, a marble group depicting a mother nursing her infant and protecting a young child. The statue was commissioned for £300 by the Broad Street Ward of the City of London in 1877, for a fountain installed behind the Royal Stock Exchange. The nurturing mother, her head adorned with a diadem, symbolizes the city’s generosity in providing clean water. Delivered in 1879, the marble quickly deteriorated and was replaced by bronze in 1897. These two works testify to Dalou’s importance and influence across the Channel.

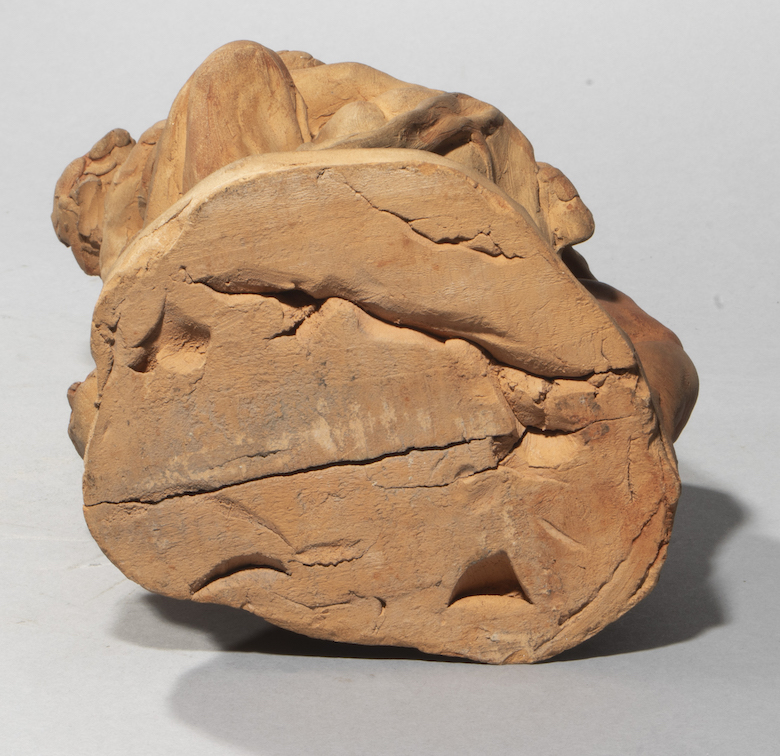

Our previously unpublished terracotta is a stage in the creative process that led to the Charity group. If we compare it with the bronze currently in place, we find the general composition has been reversed and the child clutching at the back of the figure missing. Modelled with nervousness and tenderness, it could be an early sketch, predating the very similar, larger one in the Victoria and Albert Museum (H.71cm). Both depict a seated woman nursing a child, while two others surround her, clutching her and seemingly competing for their mother’s breast. Inspired by scenes he observed in his home, Dalou posed models – young women, babies and children – to study the right gesture, that of the most moving of relationships between mother and child.

The sculptor’s virtuosity in modelling clay results in an emotionally-charged scene in which the bodies are bursting with flesh and life, and the mother, head lowered, surrenders herself to an outpouring of goodness, the whole ideally reflecting the process of sculpting, from sketch to finished work. Thanks to the writings of his biographer, Maurice Dreyfous, we know that Dalou did not systematically keep his sketches and was instead inclined to destroy them. This first sketch, magnificently preserved and so fresh, is all the more precious, and completes the corpus of preparatory studies for the London sculpture commissioned and executed in 1877.