Description

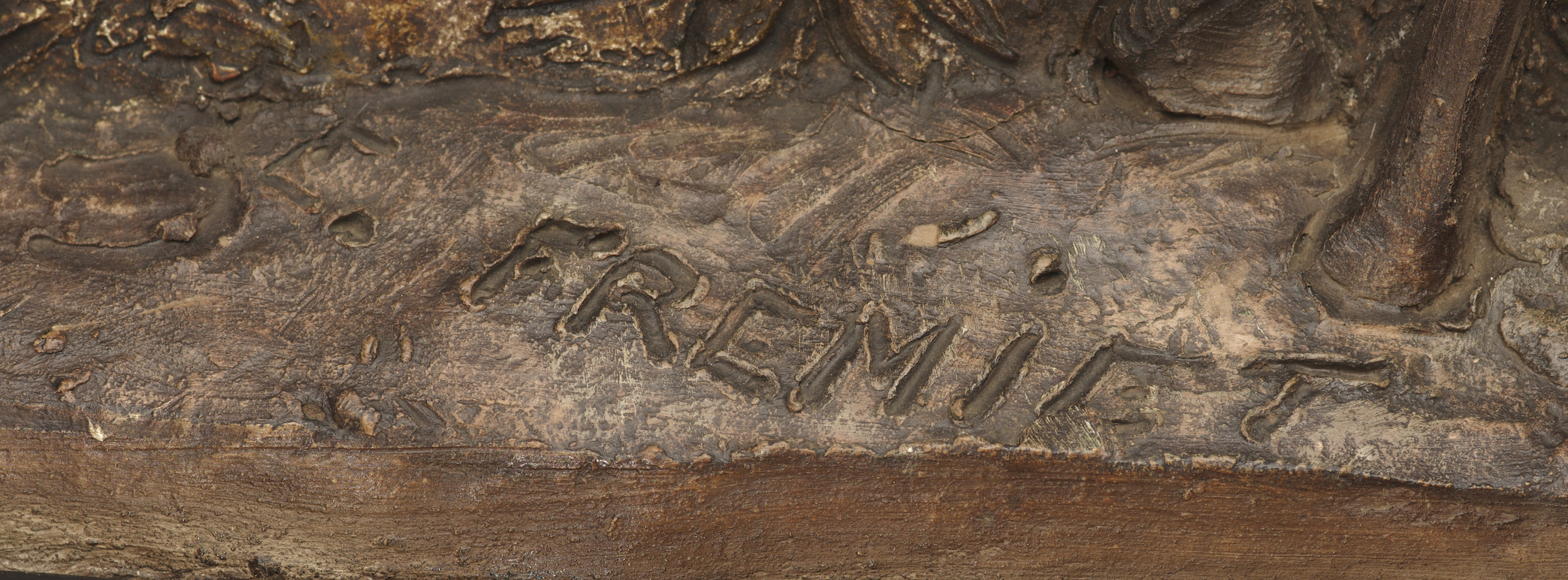

Frémiet’s eclectic style has often been noted, as in this comment: « Whoever undertakes to write the history of art in the 19th century will be baffled by the qualities of adaptability that make it impossible to recognize the chisel or other carving tool of this great artist, who, constantly variying his style, succeeded in achieving triumphs in the most contradictory genres – Who would suspect, for example, that the author of the Cheval de Montfaucon, of the Faune jouant avec les ours alléchés par le miel, of l’Homme à l’âge de pierre is the author of the modest and distinguished Jeanne d’Arc » (1875 Véron, p 87). And so it is with this original terracotta, totally atypical in his repertoire, which the sculptor has proudly signed as a unique piece.

Of all the saints in France, the former soldier Martin of Savaria, who became a monk and then third bishop of Tours, is without doubt the most popular. Countless churches, abbeys, parishes and communes honor his memory. Celebrated as early as the 4th century by his first and most fervent biographer, Sulpicius Severus, this Christian « truly worthy of the apostles » made a gesture that particularly caught the attention of artists: « forever famous in the annals of the church », he divided his cloak at the gates of Amiens in the year 334 and gave one half to a poor man, naked and shivering with cold, in the midst of a winter that was more severe than usual. The religious revival of the 19th century, particularly under the July monarchy but especially in the 1840s and 1850s, included Saint Martin, even though he would be unable to regain the power he had once commanded. In the first half of the century, abandoned churches were rebuilt and furnished, and images of Saint Martin were commissioned to be placed in the churches dedicated to him. The State replaced the « ymagiers » who had disappeared, called on painters rather than sculptors, and distributed its mounted Saint Martins, commissioned from painters in Paris and at the Salons. The list is lengthy; among the most famous are Gustave Moreau (1826-1898), Victor Mottez (1809-1897), Jean-Victor Schnetz (1787-1870), Évariste-Vital Luminais (1821-1896), Luc-Olivier Merson (1846-1920),.. All these painters, contemporaries of Emmanuel Frémiet, helped spread the legend of the saint.

It is therefore hardly surprising that the sculptor was also inspired by this religious revival around the figure of Saint Martin. With this sculpture, he contributed in his own way to reproducing the episode of the gift of the cloak. But rather than an ostentatious sculpture like the one that adorns the Palais de Justice in Amiens, La charité de saint Martin by Justin-Chrysostome Sanson (1833-1910), he chose here a format and style conducive to private devotion. Directly inspired by the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages in its rich polychromy, gold background and inlaid lettering, this original terracotta is a singular sculpture, intended for piety and contemplation. It is the work of a sculptor known for his passion for history, for his documentary research on the Middle Ages, undertaken as a veritable archaeological quest, as was the case for the models of Joan of Arc on Horseback (1874), Saint Gregory of Tours (1878), or Saint Michael Slaying the Dragon (circa 1897).