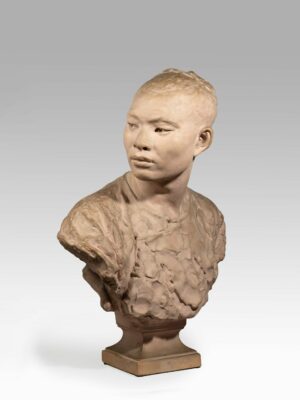

Jean-Baptiste CARPEAUX

(1827-1875)

Born in Valenciennes into a modest family, Carpeaux settled in Paris with his parents in 1838. At a very early age, he grew a passion for drawing, architecture and modelling at the free school Petite Ecole royale, before entering the workshop of François Rude and thereby being given access to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. It took him seven years to be awarded the grand prize of sculpture in 1854. He then left for Rome for a four years’ stay at the Villa Medicis where he discovered the masterpieces of Michelangelo, one of his prominent models. Back in France, he created a bust of Princess Mathilde and started working for the imperial family. He moreover gave drawing lessons to the only son of Napoleon III and Eugenie de Montijo.

The Empress commissioned the artist to create a bust and full-length portrait of him, as a little boy smiling and playing with his dog, Nero (Musée d’Orsay).

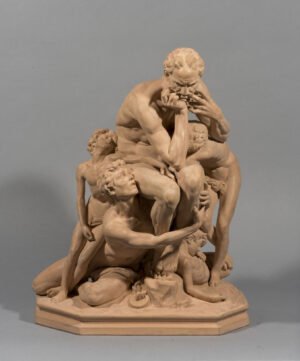

Known for his busts, imbued with realism and a gentle candour, Carpeaux appears as the perfect illustrator of the romantic spirit, both in his career and his artworks. His artistic approach, which contrasted sharply with the neo-classical trend, is characterized by an important study of movement, its realism and a taste for dramatic scenes mingling aesthetic dimension and emotion. In fact, the sculptor embodied the image of an often misunderstood artist, seeking to transform everyday life, the present into new myths putting his art at the service of senses and nature. Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux who received many public commissions realized the decor (featuring sensual and smiling figures) of the south facade of the Louvre’s Pavillon de Flore, which had been rebuilt by the architect Hector Lefuel. In 1861, Charles Garnier who had just been entrusted with the design of the new Opera, commissioned the creation of a group of three figures inspired by ballet for the building’s facade. Ignoring the architect’s advice, Carpeaux designed a joyful round of nine dancers, naked and vibrant. His artwork was a true scandal and gave rise to major debates.

The 1870 War, the fall of the Second Empire and finally the artist’s death in 1875 prevented ‘The Dance’ from being removed.